The Mundane, the Profound, and the Avuncular

Several years ago, during my initial visit to Kate's place back in Iowa City, one of the first things I noticed was a large, framed photograph of a weary-looking older guy sitting in front of a weathered red barn. It was a striking picture, actually, with long, late-afternoon shadows stretching through the frame and the dark silhouette of a cow in the foreground. Before I could even ask, Kate explained that the man was her great-uncle Lewis, and that the barn was on the cattle ranch where he'd lived. The photo itself, she told me, was taken by her uncle David, who -- along with her aunt Kathleen and two cousins -- still lived on the ranch, just outside the small river town of Rio Vista, California. "They are the absolute coolest uncle and aunt you could ever imagine," she gushed, and went on to tell me how much she loved visiting there and spending time with that part of her family.

Several years ago, during my initial visit to Kate's place back in Iowa City, one of the first things I noticed was a large, framed photograph of a weary-looking older guy sitting in front of a weathered red barn. It was a striking picture, actually, with long, late-afternoon shadows stretching through the frame and the dark silhouette of a cow in the foreground. Before I could even ask, Kate explained that the man was her great-uncle Lewis, and that the barn was on the cattle ranch where he'd lived. The photo itself, she told me, was taken by her uncle David, who -- along with her aunt Kathleen and two cousins -- still lived on the ranch, just outside the small river town of Rio Vista, California. "They are the absolute coolest uncle and aunt you could ever imagine," she gushed, and went on to tell me how much she loved visiting there and spending time with that part of her family.A year or two later I finally got to see for myself when Kate and I traveled out there to stay on the ranch for a few days, and I'll be damned if it wasn't true -- David and Kathleen really were that cool. Not only that, but the picture of uncle Lewis wasn't a fluke, either. David was a seriously gifted photographer, and the walls of their home were covered with photos he'd taken of things as mundane as life on the ranch and as profoundly beautiful as some of the forests and mountains and landscapes he was so fond of. And on top of everything, he loved baseball! He coached little league in town, and went with his family to big league games in San Francisco. (And even if I didn't fully appreciate what it meant to be a Giants fan, what did I care? It wasn't as if he liked the Yankees or anything.) Anyway, the point is that Kate was right. I quickly found myself feeling a little envious of her and her cousins, and wishing I was part of their family. This feeling soon passed, however, since Kathleen and David made me feel so instantly welcome it was as if I was family already and had been visiting the ranch all along. It was beautiful out there, too, with rolling hills and eucalyptus trees and clear dark nights with what seemed like millions of stars. I didn't want to leave.

Kate and I spent a couple of days there again just this past December, the highlight of which was a slideshow that David had spent the afternoon putting together. He'd set up the projector in the small, unheated poolhouse, and the sixteen or eighteen of us that had gathered at the ranch for the holidays bundled ourselves up and sat out there on that cold, clear, starry night and watched the images of him, Kathleen, and their friends in what were clearly younger days, hiking and camping in some of the most magnificent places I'd ever seen. There were the men, bushy-bearded and sunburned, climbing up some impossibly steep canyon wall in one slide; there was Kathleen edging along some narrow, crumbling ledge while smiling serenely in the next. I'd grown up in New Jersey, and was only vaguely aware that such places even existed. It was all just so incredibly... cool. Every once in a while Kate nudged me and arched an eyebrow knowingly, as if to say, "see?" All I could do was nod in complete and utter agreement.

Just two weeks ago, David died in an automobile accident. Kate called me from work with the news, then came home early and cried all night. In the five years I've known her I'd never seen her like this, and her first and only impulse was get out to the ranch as soon as possible and to be with Kathleen and her cousins. We booked a flight and were on our way to California a day and a half later. Kate spent a lot of time helping out around the house, and we met dozens of Kathleen and David's friends. I learned more about David, too -- more about his wilderness adventures, his photography, about what an enormous impact he'd made on so many people. And we went to the memorial service last Tuesday, which was held at Egbert Field, Rio Vista's little league diamond. It was the only place big enough to hold the hundreds of people that showed up. There, I learned even more about the ways he'd touched the people in his life, and heard his friend Andy tell a story about him that was one of the funniest things I'd ever heard. (Andy also put together a photo tribute to David which you can see here.)

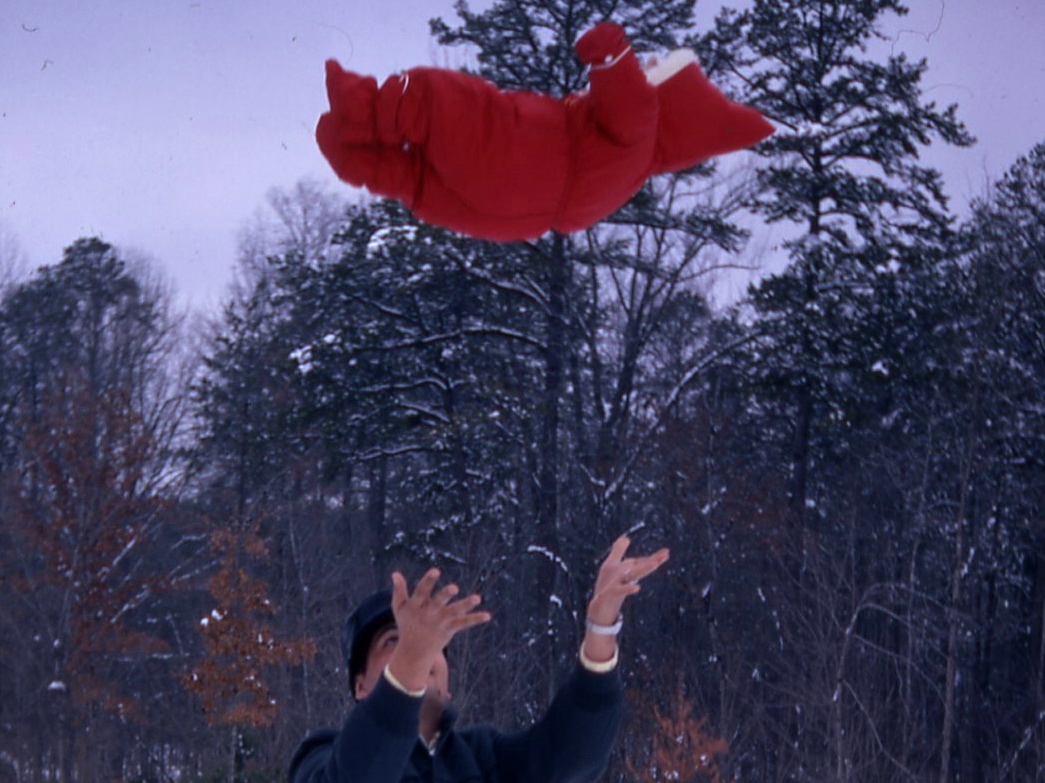

Only two weeks earlier, my younger sister Mel and her husband Rob out in California had their first child, a little boy they named Nathan. Since our annual travel budget is pretty limited, and since we would already be nearby anyway, it seemed only natural that Kate and I also spend a couple of days seeing my newest nephew, and so we arranged to spend a day or two with them at either end of the trip. It turned out that Nathan was just as precious and adorable as Mel had claimed, and despite my nervousness about him wriggling free or breaking in my arms, she let me hold him for a few minutes. He was so tiny, so fragile, so beautiful! (I brought earplugs, of course, reasoning that at least one person in the house ought to get some sleep.)

But bookending something as sorrowful as David's memorial with something as joyful as seeing little Nathan felt vaguely inappropriate, the juxtaposition unsettling. After all, these elemental but opposing forces -- birth and death, the only two things any of us can ever really count on! -- are phenomena at once so mundane as to be banal yet so deeply profound that attempts to make sense of them lie at the root of almost every human religious impulse. I found myself looking for explanations, for ways to reconcile how our lives could be framed at once by such happiness and such grief, how they could even coexist. Needless to say, I didn't come up with anything. Plenty of individuals far smarter, and any number of writers far more eloquent than I'll ever be have pondered these things for whole lifetimes and still come up short, so I'm not going to pretend that I have anything to add.

After some reflection, though, I realized that my desire to comprehend these things was misguided in the first place. The intensity of the sorrow and loss felt by David's family and the pure maternal joy that fills Mel every time she looks at her new son are experiences that I will never know, nor probably ever even understand. Anything I'd try to write about these things would ultimately ring hollow. Eventually, however, I realized that what I could do is to endeavor to always remember the importance of family, to cherish time spent with them, and to hope that someday, one of my own nephews or nieces might be able to say to someone -- perhaps even their own future mate -- "hey, I've got this really great uncle that you've got to meet." Sure, I know I'll never be half as cool as David (and probably much less than that, given the deficit I'm starting out with), but it's something I can certainly work at and aspire to. And maybe, just maybe, in my own little way, I might be able to pass along to them some tiny spark, some momentary glimpse of the warmth and humor and generosity of spirit that David evinced, the depths of which I was only at the very beginning of understanding myself.

Now, if I could do that -- well, that would be very cool, indeed.

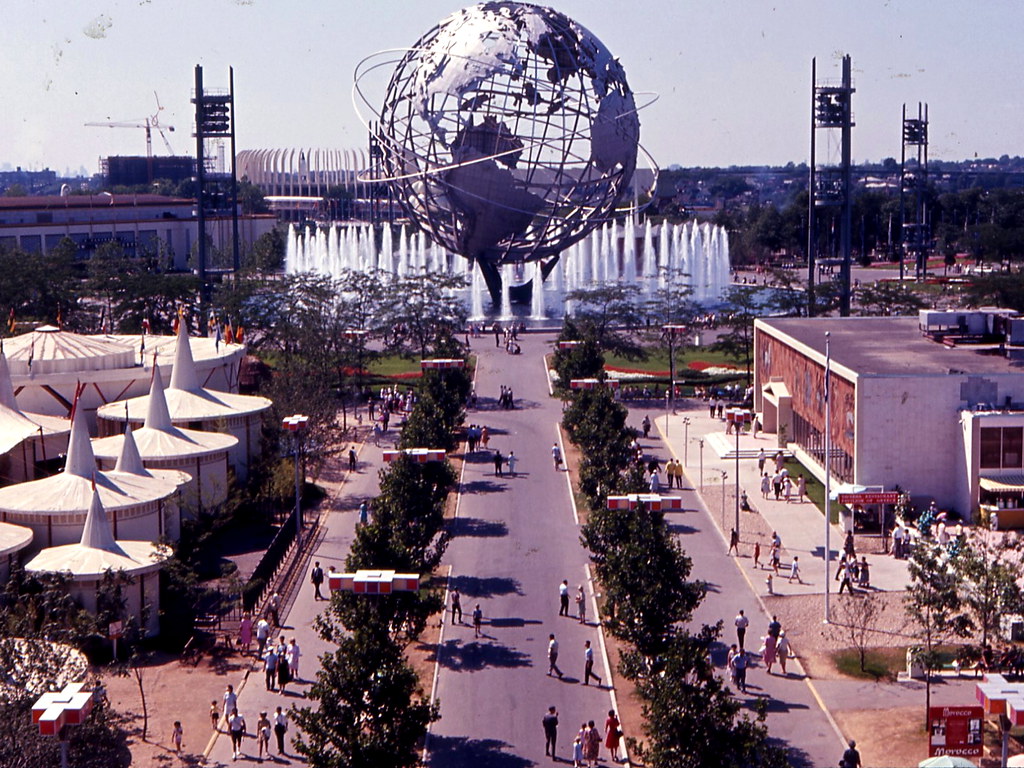

Here are a few pictures from the ranch. Spring, obviously, had arrived.